Published December 2022, Plastikcomb Magazine issue #5

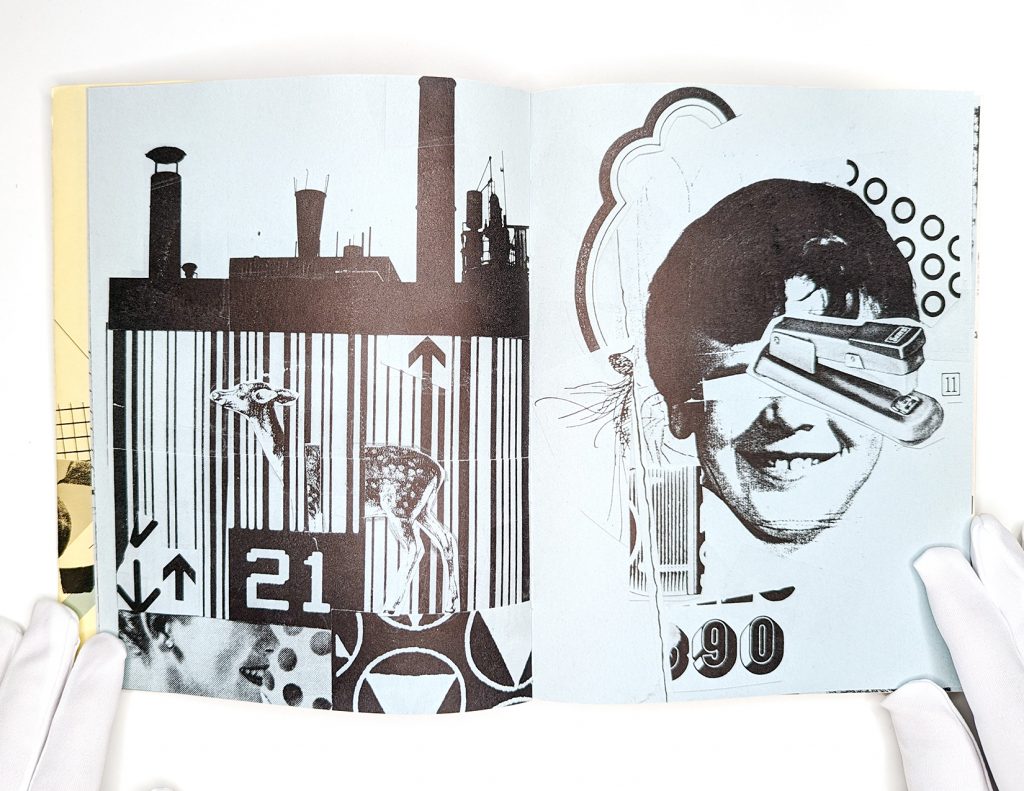

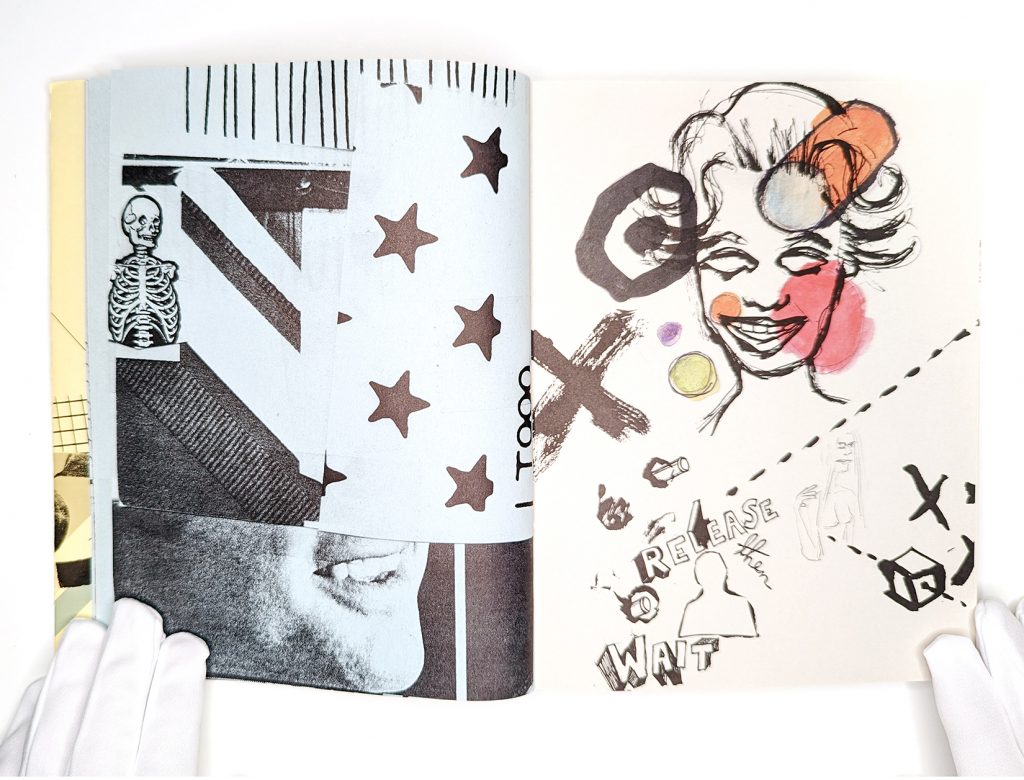

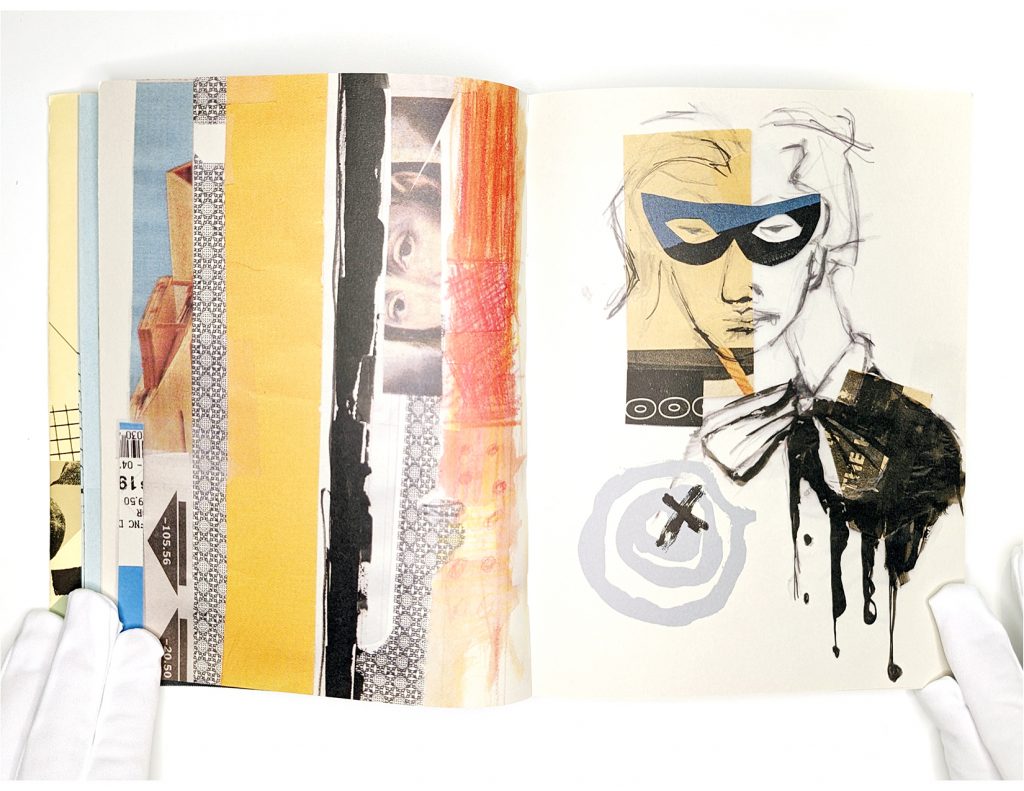

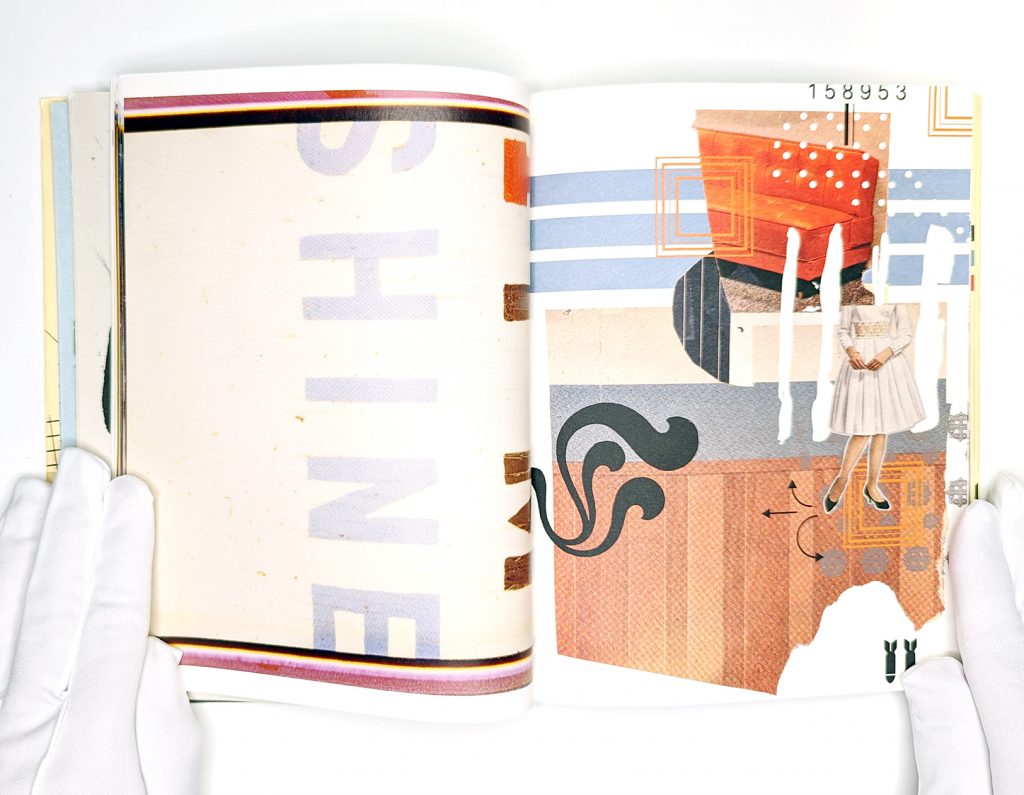

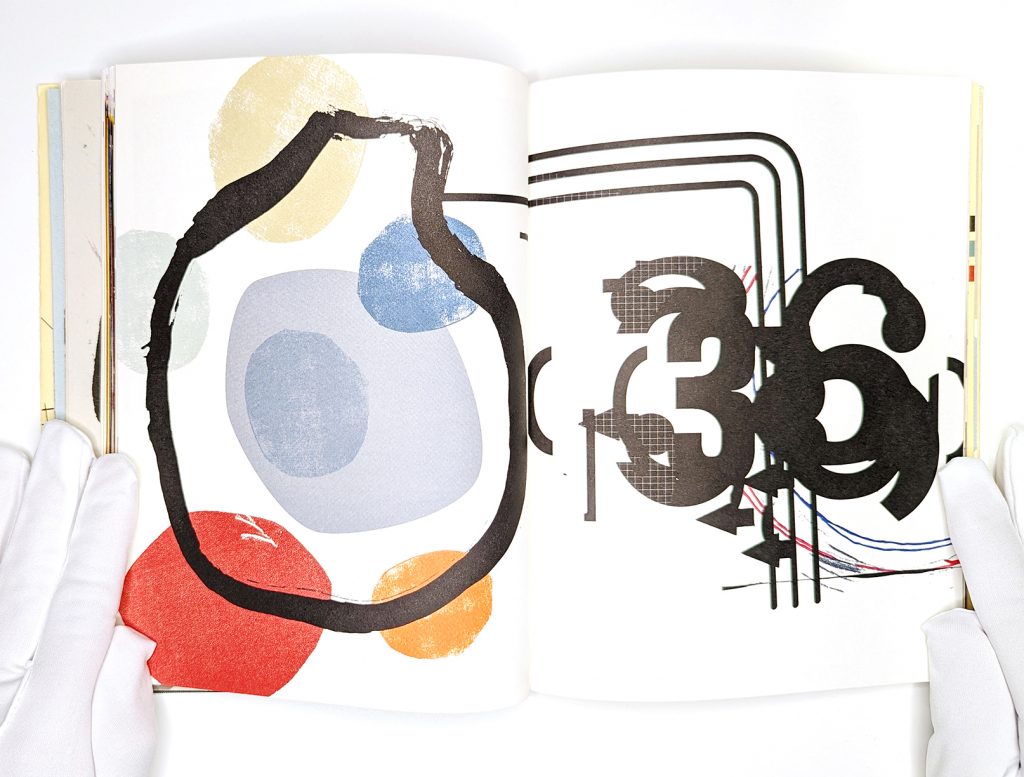

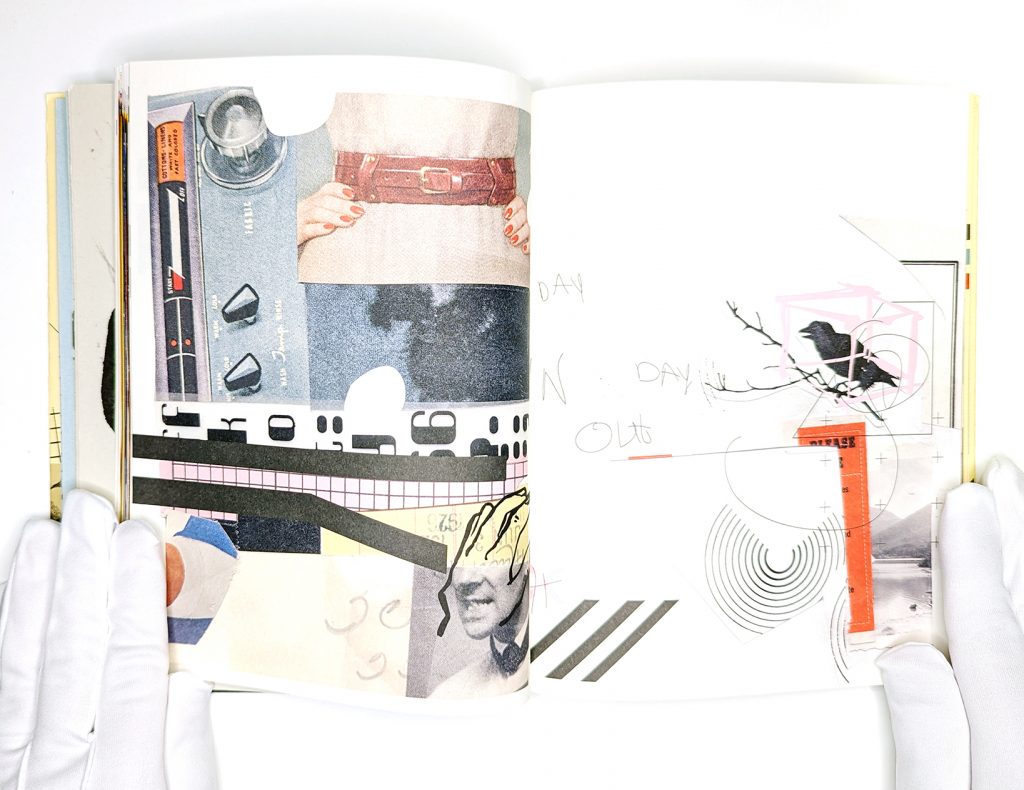

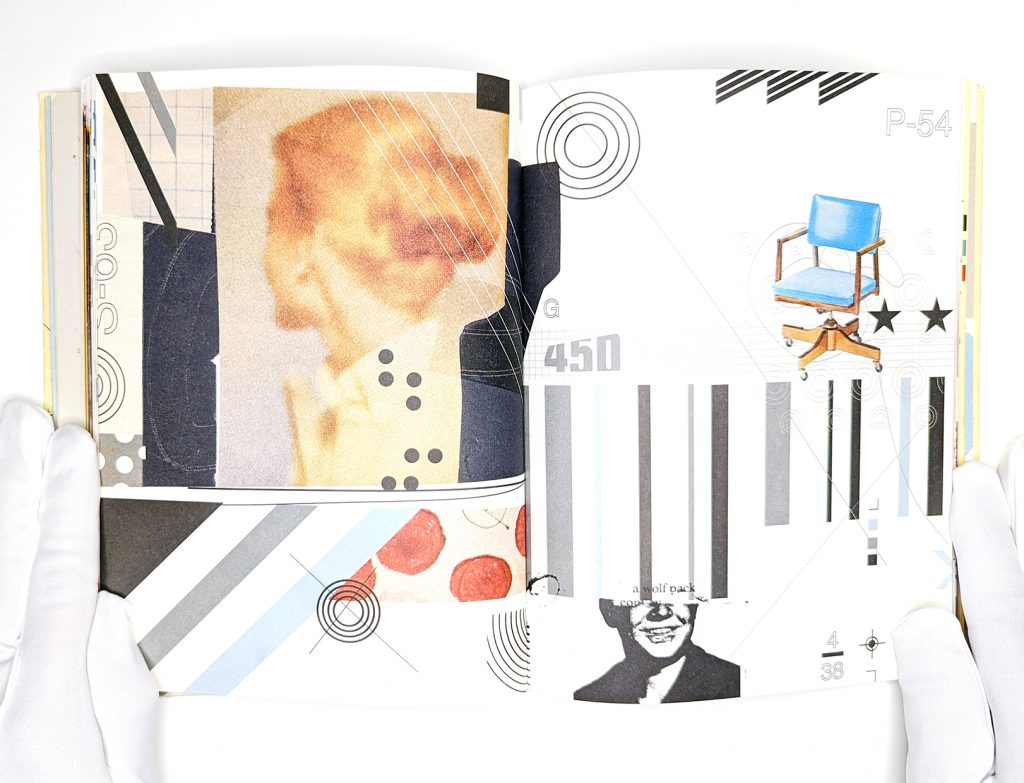

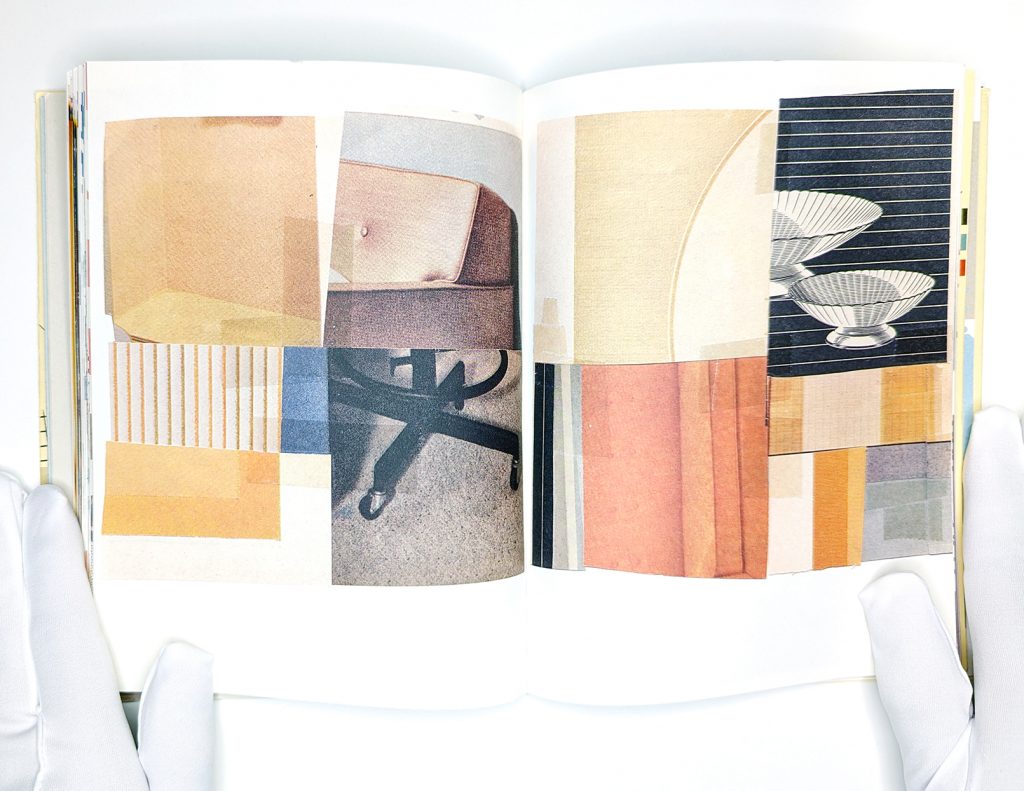

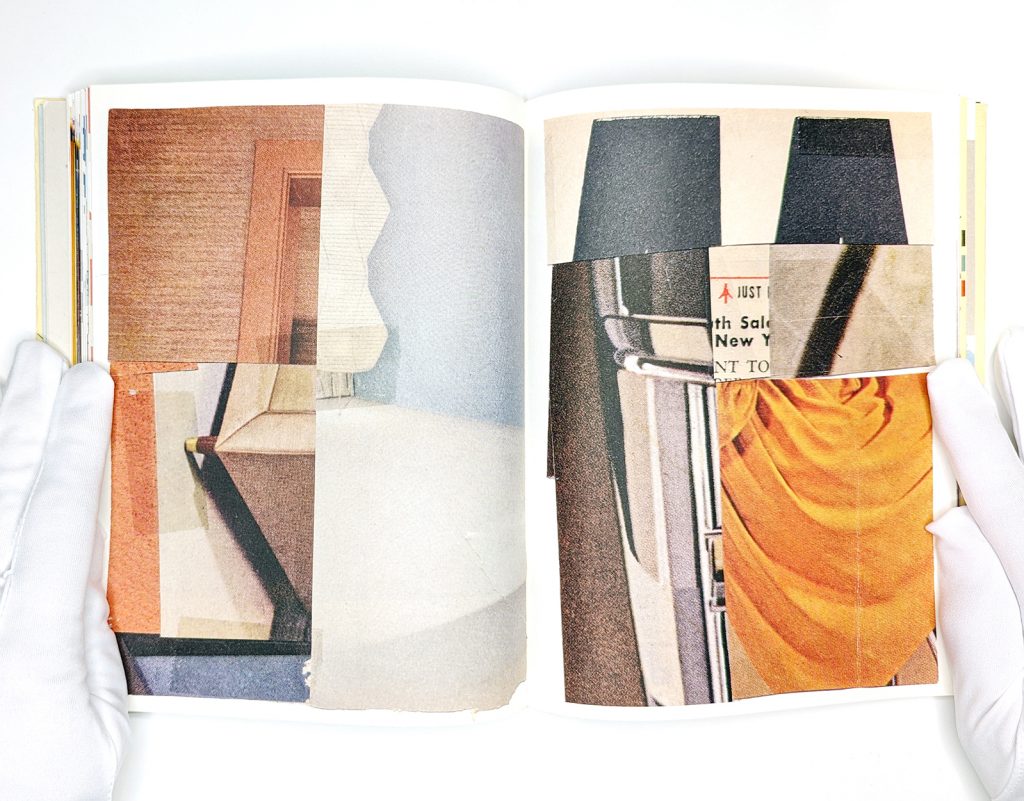

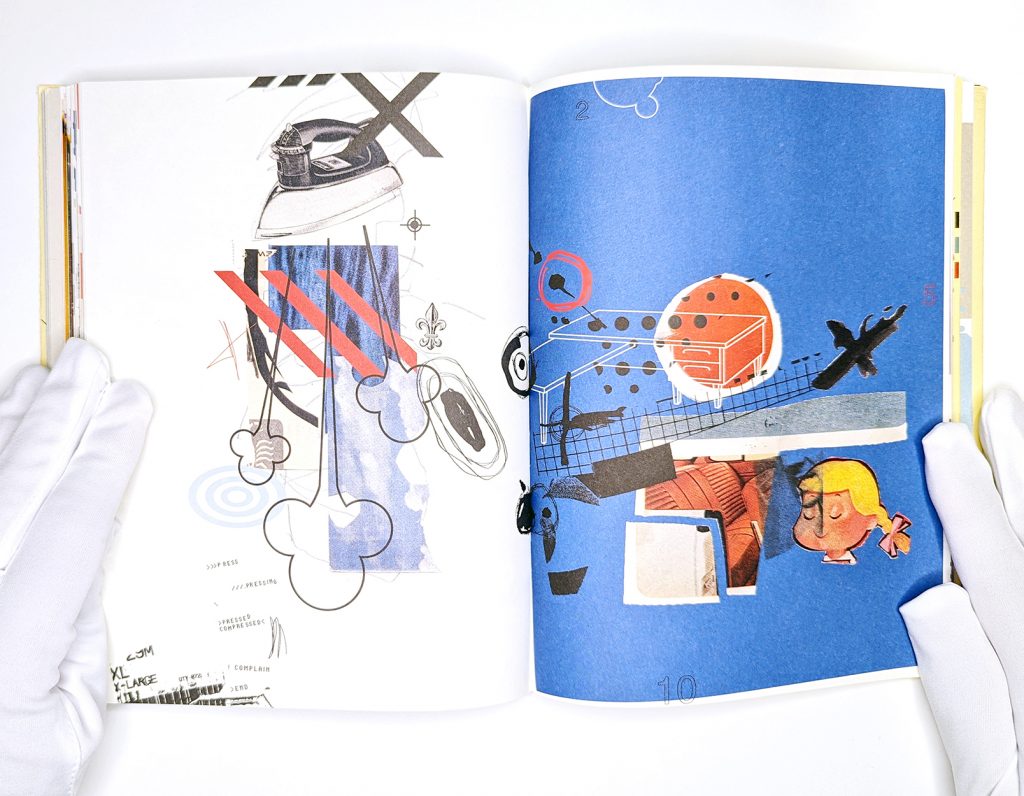

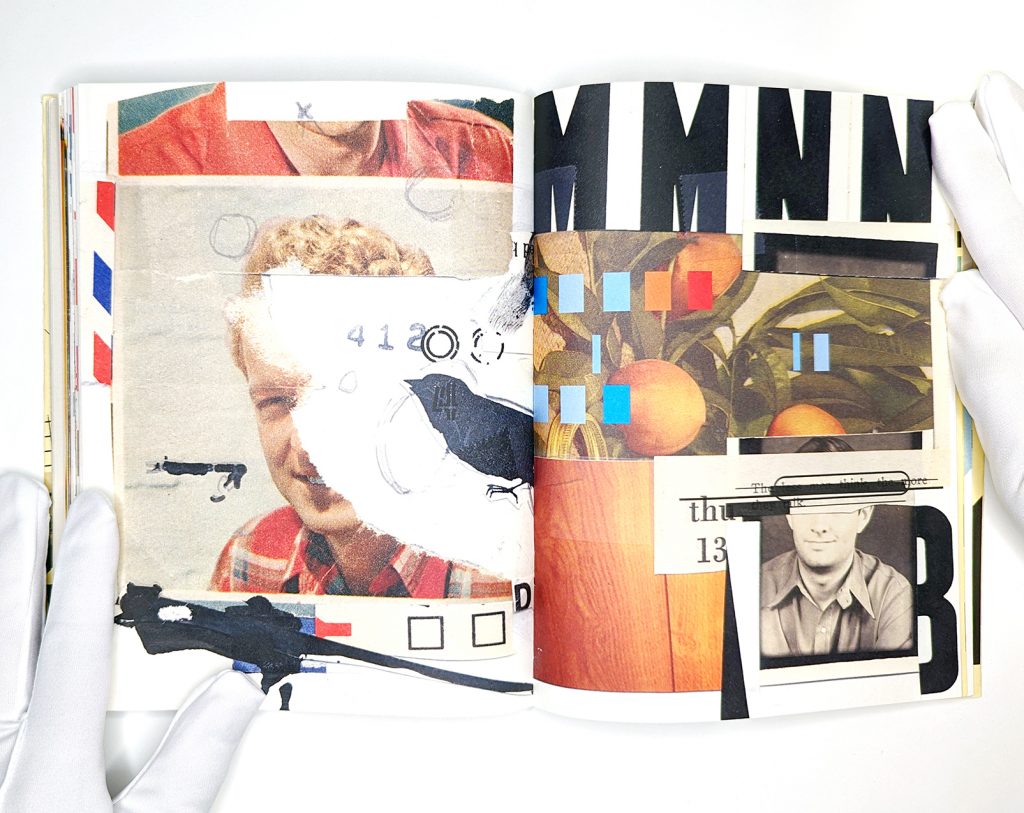

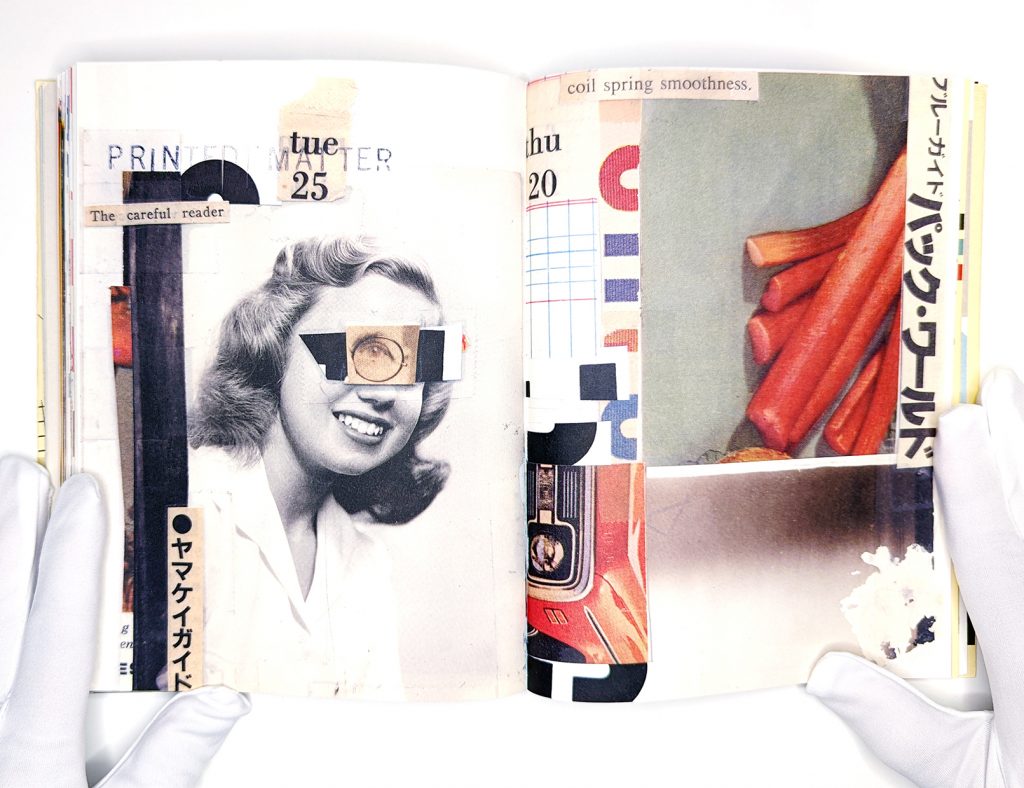

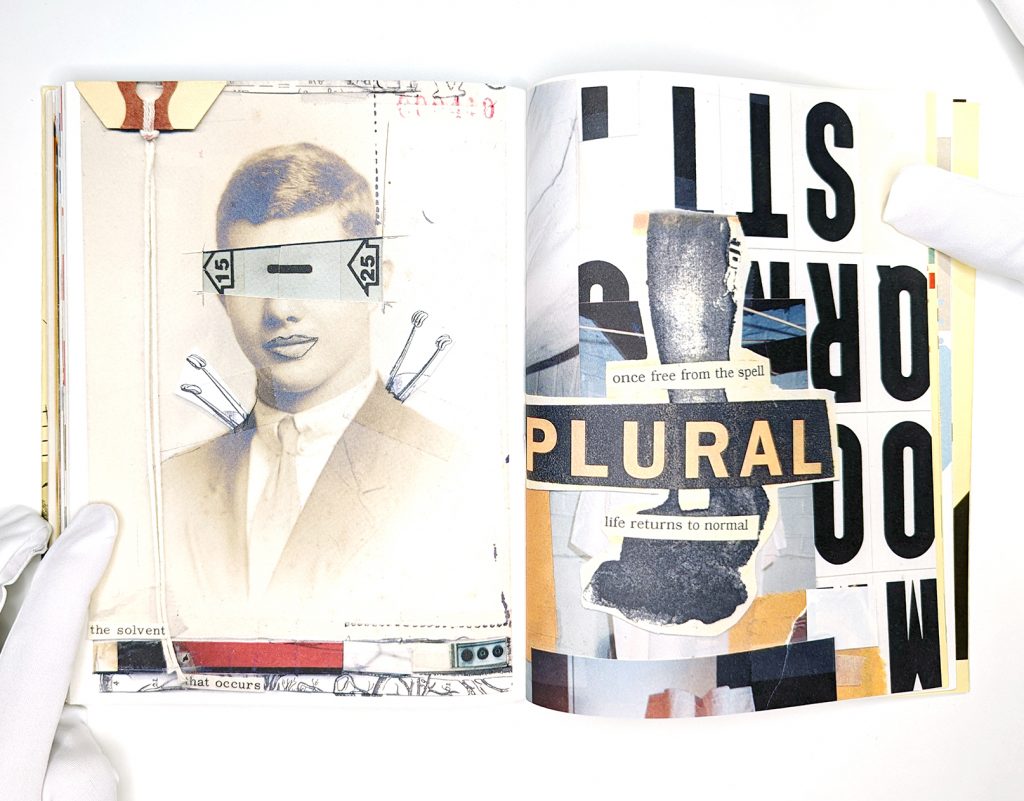

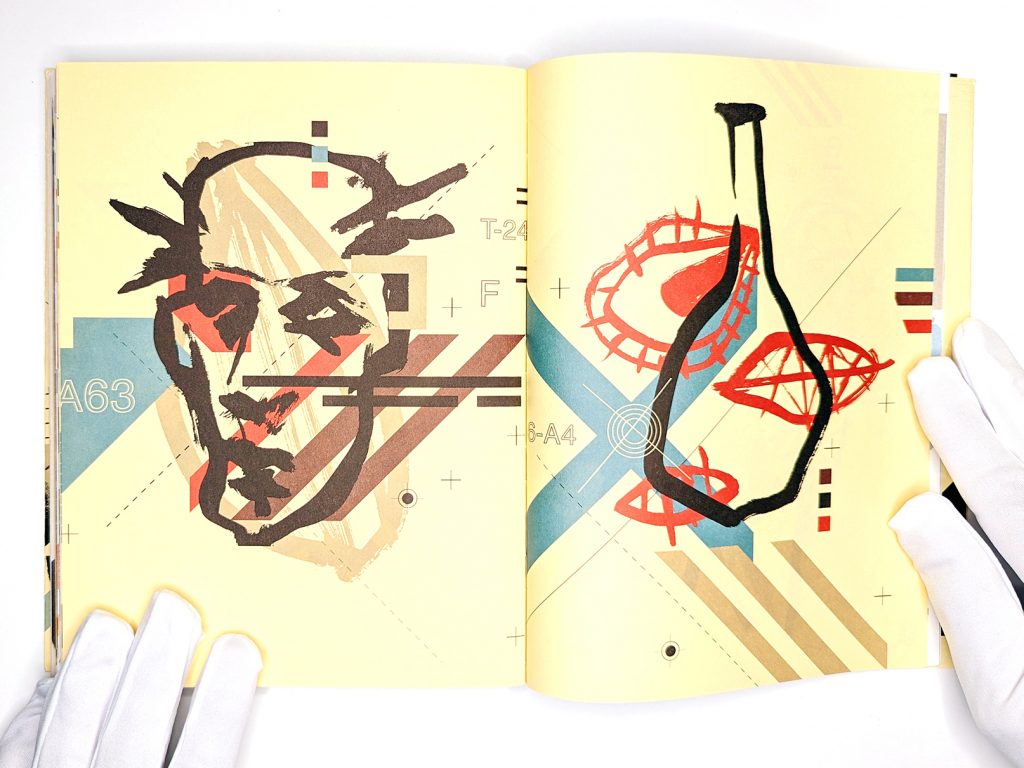

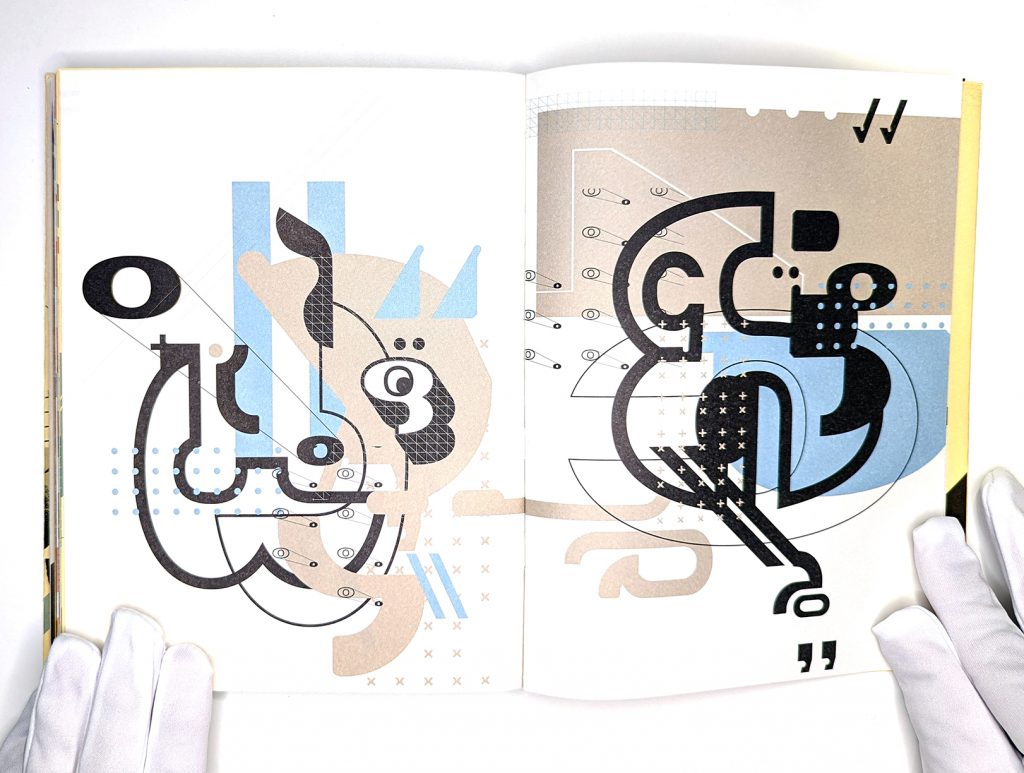

Nearly two decades since its publication, Charles Wilkin’s INDEX-A remains a grand source of inspiration for artists, graphic designers, and illustrators. Although, the way Wilkin puts it, “I was just trying to make beautiful pages … things that interested me, things that [reflected what was] happening in the moment”, one might think his aim was to simply make another picture book in an already played-out market of picture books. And yet, INDEX-A has outshone its author’s unpresuming account. In point of fact, it is a grand and wholly captivating publication. Fevered, analytical, experimental, and packed with a disarming cast of objects, textures, and characters, thumbing through my weathered copy of the 6 1⁄2 × 8 1⁄2 × 5⁄8-inch volume is akin to spending time with a sage, grizzled elder. Though the visual grammar of INDEX-A recalls a bygone period of graphic design variously christened “post-modern”, “grunge”, “deconstructed”, “eclectic”, “vernacular”, “untutored”, or “lowbrow”, page for page, Wilkin’s collages are as compelling as ever.

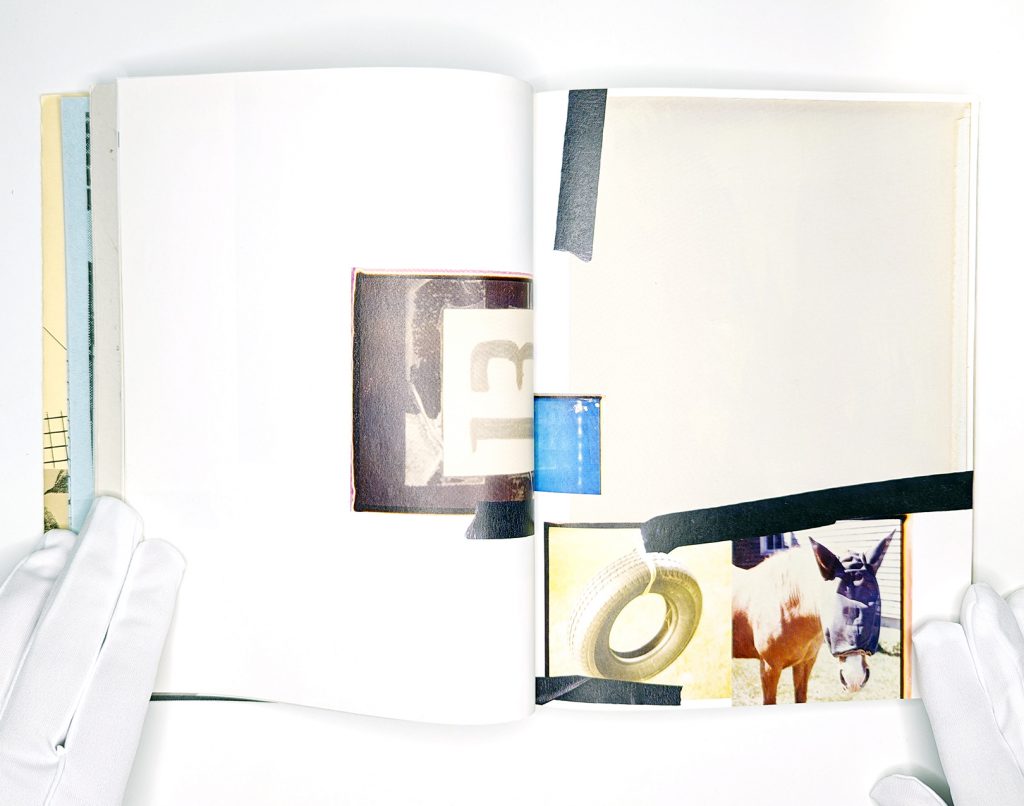

The book began as 10 spreads accompanied by a rough outline; it was pitched as “a … giant sketchbook” that would merge and showcase, albeit “loosely”, Wilkin’s thoughts and experiments as a professional graphic designer. He explains, “I didn’t want it to be a greatest hits book of everything I had done up [to] that point. I wanted a lot of new stuff and I wanted to explore things I had done in the past.” For example, “the Polaroids [in the] book were all [shot] specifically for [the] book. I bought a Polaroid camera … bought film and, I trolled New York for months taking photos.” Most of the imagery was cut by hand, scanned and some were completely digital. “The drawings … came about because, I felt [there was a need for] more handwork in the book. I had always [done] weird ink drawings. In the 90s, I was [also designing] typefaces and so, I would draw … letters.”

Wilkin approached several publishers and, Gestalten, would ultimately publish INDEX-A. He recalls Gestalten’s Founder and CEO, Robert Klanten, as being “the only one to respond”. The two met, reached an agreement for completion of the book, and the rest is history. Wilkin notes Klanten’s forbearing design input, targeted editing, and assistance with pagination. The result? A nonstop serving of reconstituted photographs, drawings, illustrations, fonts, hand lettering, handwriting, shapes, patterns, and textures; a veritable treasury of unrelenting visual production. Wilkin stresses: “The book itself … is a collage”.

From his home studio in the Catskills, there is a desk overspread by clippings (remnants of earlier collages) that partially veil a green cutting mat, a considerable stockpile of old magazines in spite of a recent clean-out; an old photocopier that has shadowed him for more than a decade, two rolls of masking tape, and a pair of tape dispensers within view. Wilkin is quick to point out that, when he began crafting collages in the late 80s, they were a reprieve from managing his hectic graphic design business, the now defunct Automatic Art and Design, which he maintained and directed from 1994 to 2019. Though he made his reputation as a graphic designer in whose hands collage and practical commercial techniques coalesced, he has since withdrawn from the field. Today, Wilkin is chiefly a collagist, a form of art he has practiced since his undergraduate days at The Columbus College of Art and Design. He calls himself an artist, which is no mere change of title. “From the beginning, I always was an artist. Even when I was a graphic designer, I would say, ‘I’m an artist.’” For this reason, he opted to name his studio “automatic art and design” – “automatic”, the leading term, emphasized his ineluctable creativity. In fact, he sees no distinction between designing and artmaking, “I was always disappointed that people wanted to put me in a box…. I’m an artist. I’m making work, [I solve] problems.” Although Wilkin understands the human inclination to classify individuals and their pursuits, he believes that creativity is – and should be – boundless.

Collage is fabrication. Establishing visual relationships among disparate elements is a precondition of the medium. There is no recipe and there are no assurances, only the artist’s vision – a sense of what could be, a sense of drift or of meaning, vague notions relative to form and fit until the moment of fit and adhesion are achieved. Riveting as they are, Wilkin’s collages are a significant labor awash with stumbling blocks and disappointment. Thankfully, neither has interfered with his visual production or his creativity. However, despite his demonstrable grasp of the medium, on days he devotes to extricating potentially useful pictorial material from books and magazines, he readily admits that he may end a workday with nothing to show for his efforts. “Some days, if I’m feeling guilty that I’m not working [or] I don’t feel inspired to make a collage … I’ll just sit with magazines and … cut stuff out and make little piles of new scraps…. But … as I work, things … get tossed aside [and added to] the pile. That’s what you see here on my desk.”

One wonders to what degree and through which perceivable strategies – if at all – Wilkin’s rubble of variously proportioned clippings would be transformed. Why submit oneself to indeterminacy, not to mention, a welter of accumulating raw pictorial material? The high probability that one would produce inscrutable artifacts is among the perils of collaging, unless making ground-level connections with viewers is low on one’s list of priorities. Discerning correspondences among elements which are at best equivocal – what Wilkin calls “perceptive reading of paper scraps” – involves a considerable magnitude of seeing and refined instinct. The tenacity demanded of the artist who must toy with placements and juxtapositions is enormous, to say the least. “The best thing about collage is that you can take all [this] stuff and … [turn it] into something better or something more idealistic … hope for the future or even just for the next five seconds…. collage is always moving … it’s … spontaneous … frenetic. Collage really lines up with my life. Nothing lasts for more than five minutes because people just have no attention span. Collage emulates that.”

Wilkin’s path from graphic designer to fine artist – the basis for his unbiased view that art and design are “interconnected”, that “we’re all expressing ourselves” – can be sewn together. The prototypical art kid in high school who was drawn to the idea of making objects that would find their way into the wider world, he knew he would become an artist. Taking the equivalent of a graphic design course in high school, Wilkin soon realized that collage and preparing mechanicals were analogous, that art and assembly (i.e., “design”) were identical. He was inspired by Andy Warhol who strode the elite and working-class spheres of fine and commercial art, Kurt Schwitters whose far-ranging capabilities spanned collage, poetry, painting, and sculpture; Lázló Moholy-Nagy, the renown Bauhaus instructor, photographer, and painter, and Robert Rauschenberg whose body of work, for Wilkin, encapsulated graphic design: “Everything about his work is graphic design…. it’s typography, it’s images, it’s technique, it’s expression. He used so many [of the same] techniques that were used by the graphic design industry: silkscreen, transfers … going to the library [and] appropriating images from the press.” He cites Rauschenberg’s 1961 First Landing Jump, a “painting” comprised of objects (e.g., tin cans, light bulb, tarpaulin, car tire, license plate, road sign/barrier, wood plank) as a paragon.

Wilkin opted to pursue graphic design because, “he wanted a career in art and … design seemed like the best of both worlds…. I could be creative, and I could make money and, I could make things that would be … in the public [eye]…. Design just seemed like a collage to me: Assembling photography and typography … and color.” It was the most logical career choice. But he recalls, “Way back [in art school], there was such a separation between the disciplines…. design students did not cross [the] hall to go into the fine art department. You were not welcome…. I took photography and, once they found out I was an advertising design student, they just … pummeled me. I think it made me a better photographer.” As early as then, he knew that gaining a working knowledge of photography – its methods, procedures, and vocabulary – would increase his chances of fruitful collaboration with professional photographers. He could hire them and converse with them in ways that would not be possible had he not taken that college course. There were no partitions. “Crossing the hall”, for Wilkin, was empowerment – his and photographers he would work alongside.

The Automatic years were noteworthy. With American Eagle, Burton Snowboards, Billabong, and Target being staple clients, and a public project like the PS 186 mural he designed with Pentagram partner Michael Bierut, Wilkin’s reputation was promptly solidified. A promising and ambitious graphic designer just out of college, Wilkin “wanted to be … well-known … but” confesses, “I honestly had no idea what that meant and how much work it required. I was … naïve [about] the business of design…. As my career rolled on, I became less interested in fame and focused on making great work that moved people emotionally…. the mural I did for PS 186 … was some of [my] best work, the kids at the school wrote a rap song about it which brought me to tears.” What was distinctive about Wilkin/Automatic? In hindsight, he believes it was his willingness to take creative risks, the kind that bigger and more established multidisciplinary studios and design offices could not afford to take. He clarifies by saying, “I also worked really hard to put myself and [my] experiences into [projects], which is why [there was] always … some … collage spin. In the beginning, I would take collages I’d made for myself, put type on them, and then sell [them] to clients. [That’s] what helped establish my voice as a designer”.

Leaving Home, Home Again

Mission statements are tired, and digital tools have made “graphic designers” of us all. In a culture that favors participation over ideas; access over goodness of fit, production over genuine craftsmanship, Wilkin is exceptional. “I never wanted to or thought I could reshape graphic design. I do think … the idea of incorporating your personal experience and [convictions were] … new [to graphic] design back then. I was taught the classic Swiss Grid [and] Form Follows Function techniques. So, in some ways, my work was a conscious choice to reject that [indoctrination and find a] new way, but I was not an innovator of that concept.” He credits the 90s grunge movement in graphic design for initiating the dismissal of authoritarianism in “serious” graphic design. “I personally just wanted to do what I wanted … and if [that] meant breaking the rules then, great! I did truly love helping clients … I still love that about design, and it’s certainly found its way into my collage work.”

But graphic design would not be the career venture Wilkin put his name to. He recalls an art teacher saying, “You’re going to be a designer and then one day, you’re going to wake up and regret it.” That art teacher was right. Overworked and disillusioned, he needed a change. “When I moved to New York, I thought I was going to make that leap from independent graphic designer, getting into … award books to … having a small studio and growing it as big as I could [grow] it and, I quickly realized, I [didn’t] want any of that…. I woke up one day [and thought], ‘I hate all my clients, I hate this work, I’m tired of running around not getting paid, everybody wants me to [get] it [done] tomorrow’ … I … felt like the commercial design world was … extracting the creativity out of me and … giving me nothing back. I had done so many things and, nothing seemed interesting anymore.” Out of necessity, Wilkin, at one point, managed a staff of three which he was unprepared to do. “Suddenly, [I was] just a manager.” As to walking away from graphic design: “When I made the decision to … quit graphic design, it was … really difficult … for me because, up until that point, I identified as that person even though my design work was well known for [featuring] collage”.

Collage has truly become Wilkin’s voice, a way for him to sort his surroundings and life experiences on paper and, while he does not equate collage with personal therapy nor considers it a means by which to solve or critically analyze contemporary life, it has well-equipped him to act like a filter. “Collage has been there during moments of upheaval … in modern culture”, a reliable gauge of cultural and aesthetic trend that remains open to interpretation. Years of practice, trial and error have made Wilkin a formidable craftsman who is, today, far more capable of adapting and responding to moments and to his available material. Though collaging is fraught with uncertainty, he has come to terms with his own creative process, so much so that he and the medium are one. “When I was in school … my teachers [told me to] ‘keep a sketchbook, keep a sketchbook’…. I would often write my ideas … or sketch them out and … when I do that, I’ve solved … the creative problem and, if I know where I’m going before I get there, I’m totally not interested…. The excitement, the … creative … release … the anxiety of making” are essential, and so is the element of surprise: “I’ll cut a book up and take what I think are the choice images” but, with a pile of images on hand, he avoids repeatedly taking stock of them. “What I’ve learned in the past about myself is, if I see images over and over again and [do nothing with them then], I’ve already come to the conclusion that [those images aren’t] going to work for me” which “ruins the whole process.” Wilkin admits that he could easily find himself in a loop and so, the perils of repeat playing visual/compositional strategies have conditioned him to push his collage making. As a result, part and parcel of his collage making process are the existential questions, “Where am I now, today, in this moment? What is this image [before] me and, how [will] I respond?” He adds, “if I’ve had [too much] time to look at [an] image [or] think about it … I can’t make anything.”

Then and Now

Photocopied, trimmed (without fealty to perfection), arranged by h(and)/or digitized (one cannot know where or to what degree and, this is part of their appeal); comprised of scribbles, inked and penciled drawings, co-opted images (e.g., black and white and/or color photographs, signage, typography, numbers, words, letterforms, hand lettering, handwriting), and supplemental images (e.g., quadrille paper, registration marks, maps, decorative patterns, more scribbling, frames, fleurons, masking tape, etc.,), INDEX-A is monumental – bold, adventurous, noisy, speculative, and relentless collaging. The corollary of Wilkin’s keen orchestration, it is also a profound catalog of the artist’s heart

and mind.

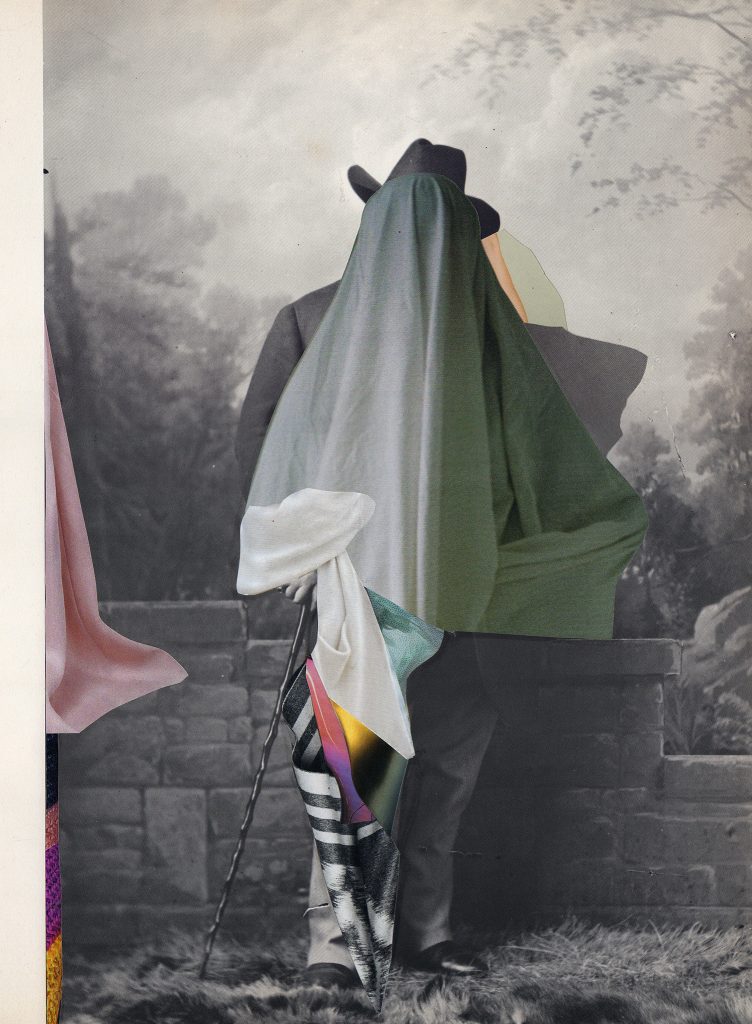

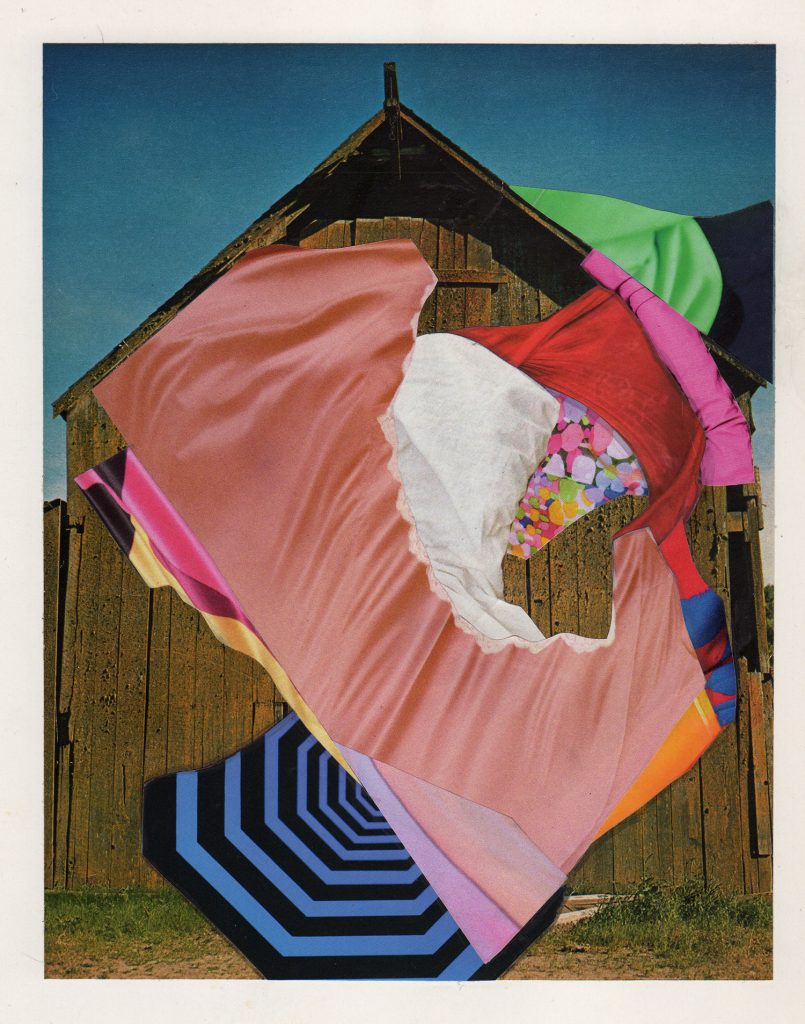

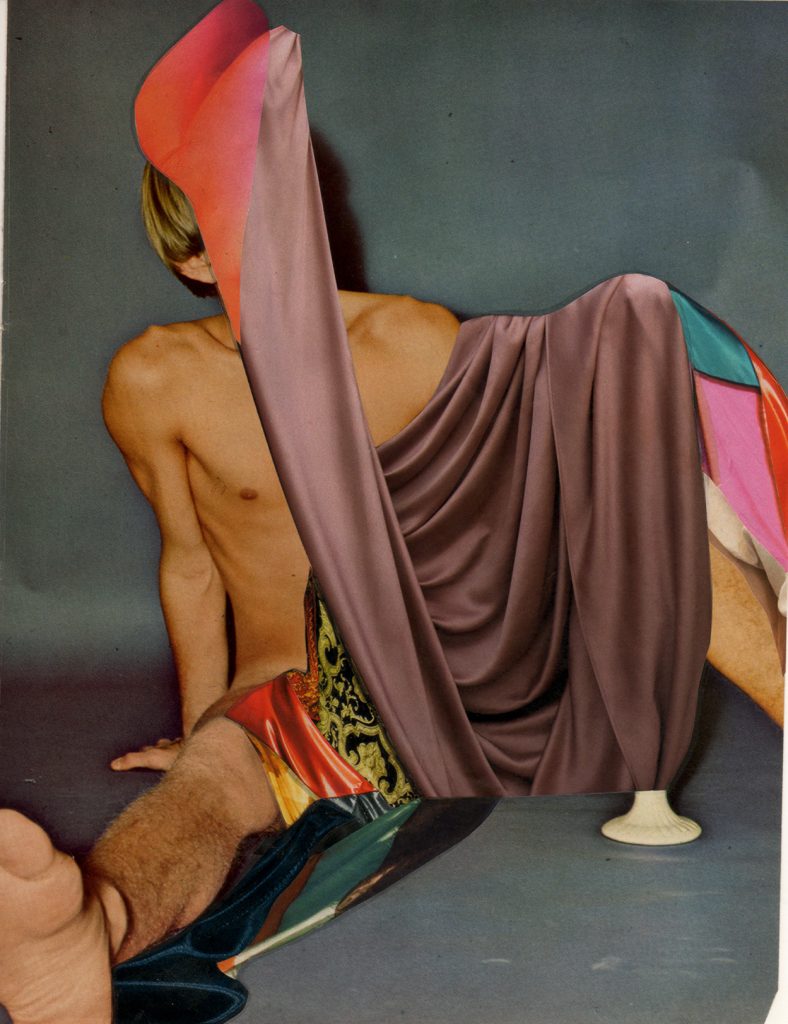

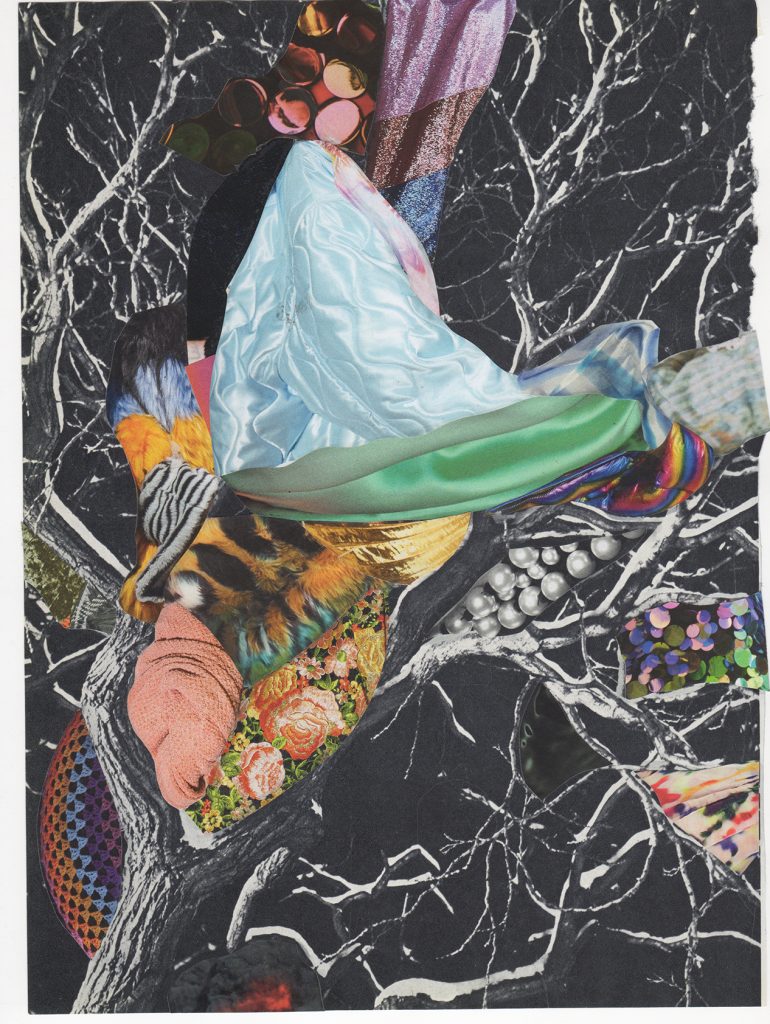

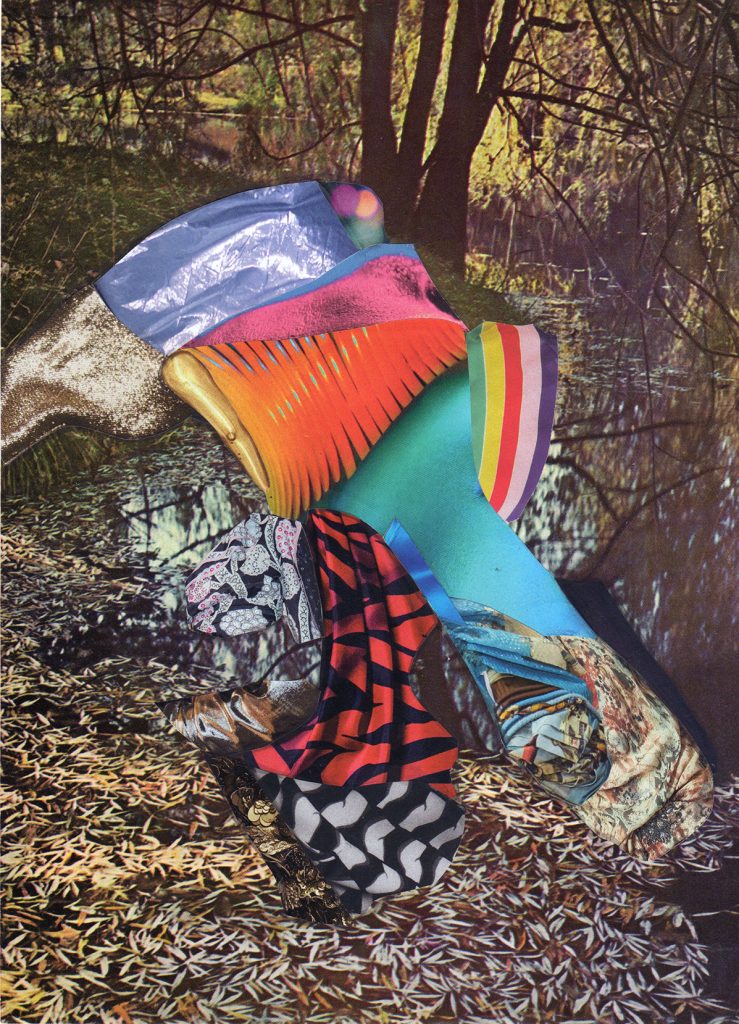

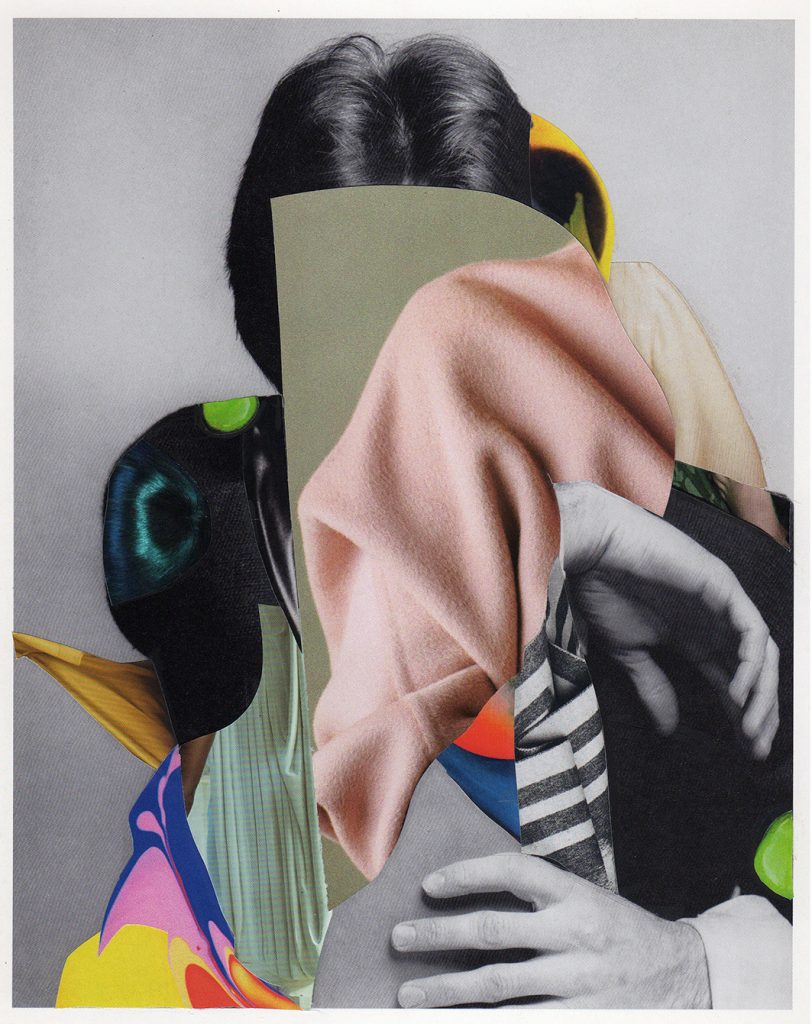

Whereas the collages featured in INDEX-A were forceful and resolute, today, the artist puts forward a strain that is at once – and to varying degrees – veiled (pun intended), scintillating, suggestive, surreal, amusing, ethereal, and mysterious. A Lullaby for Christo’s Ghost, Art 4, Hexes, June 2021, Tethered, When I’m Dead My Ashes Will Sparkle In The Sunlight, The Time It Takes Is A Reasonable Explanation For Superstition, are rhythmic and characterful pictorial essays, each incorporating a selection of textile cutouts placed over static black and white or color backdrops, arrayed in defiance of gravity. This body of work highlights Wilkin’s penetrating sense of formal relationships, his rapierlike command of placement, juxtaposition, orientation, pattern, texture, shear, and cropping. They are a testament to his evolving, indefatigable artistry.

Although Wilkin occasionally draws on his background as a trained graphic designer for 2Queens Coffee merchandise, the coffee shop he and his husband, Martin Higgins, own and operate in Narrowsburg, New York, he asserts that, when he retired from graphic design, “people were often defined by the medium or career they chose. Since I worked mostly as a [graphic] designer … that [was my label and], some [people] assumed I was … an illustrator. I always hated [that because] for me, it was all art and art making, the application was the only difference. At the time, the fine art world really was not welcoming to designers…. when I started showing my collages in galleries, I had to redefine myself publicly … though nothing had really changed.”

Hindsight, Danger, Magic

Thinking back, Wilkin matter-of-factly states that INDEX-A “really wore me out…. It did what I wanted, it got me more press and interest [but] it became … overwhelming and, by the mid-2000s … I was creatively exhausted. I was really struggling with creative block. It was just too much … I hated where … my career [was headed] and, my personal work was terrible. So, I woke up one day and I said to Martin, ‘We need to go skydiving today, today! I need to scare the shit out of myself, I can’t get out of this creative block, I can’t do it anymore … I need to stare at the ground coming at me at 1,500-miles an hour and, if I hit the ground, that’s fine. If not, maybe it’ll change everything for me.” Martin refused to do this. “I was, like, fine. I’ll do beekeeping … I was looking for something dangerous.”

An artist and one-time professional graphic designer, Wilkin’s evolution is life-affirming, a reminder that nothing is certain, that passions can fall away, that the truth about who we are – what nourishes us – can be deferred, but not for long. As a proper beekeeper, he gained so much more than the danger he originally sought, something radically different from the life he knew and built: “The bees gave me … a better sense of myself [and] this world”, they gave him empathy “and [greater] understanding … a [clearer] vision of how everything’s connected”, not just in terms of ecology or global warming – all of it. The bee community is astounding because they work so well together “to make one magical thing [and] that’s the corny metaphor of it.”

Though Wilkin plays down a direct connection between beekeeping and collage making, it’s conceivable that the magic he sees in the apiary is the very same magic that sustains his unparalleled artistry ✘